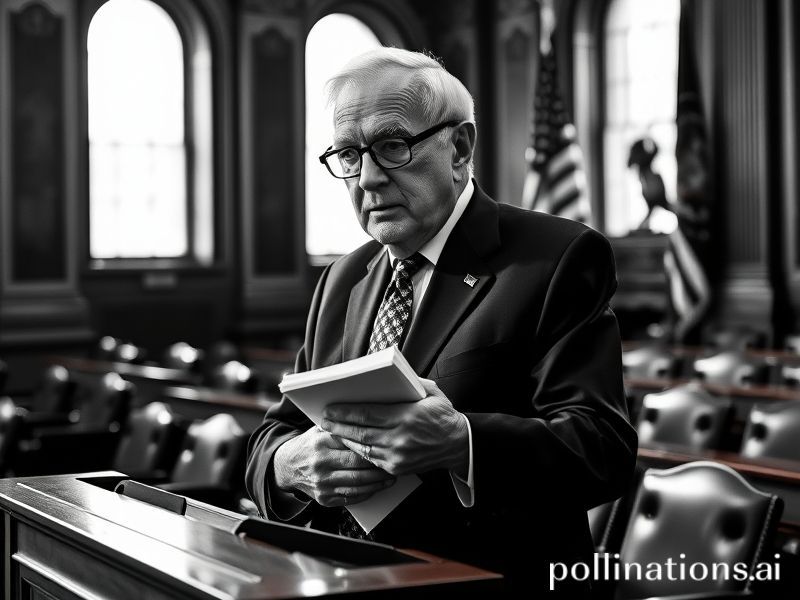

chuck grassley

In the grand, gilded circus tent that is the United States Senate, where septuagenarian lions still roar and octogenarian tight-rope walkers refuse to install a net, one act keeps drawing the world’s gaze: Chuck Grassley, the 90-year-old Iowan who has spent more cumulative hours on the Senate floor than most of us have spent on commercial airlines. To Europeans watching their own parliaments cycle through leaders like seasonal menus, Grassley is less a politician than a living fossil—part trilobite, part T-Rex—still somehow roaming the Cretaceous swamp of American legislative procedure.

Grassley’s latest feat of longevity came this spring when he announced he will seek an eighth term in 2028, a decision that sent shivers down the spines of actuarial tables from Tokyo to Toronto. Should he win—and Iowa’s fondness for incumbency is the electoral equivalent of gravity—the Senator will be 95 when he is sworn in, older than the state of Israel and several United Nations member states. The global implications are not small. When Grassley was first elected, in 1980, China’s GDP was smaller than Spain’s; today Beijing calculates that by 2028 the old Hawkeye will have personally overseen every U.S. farm bill since the invention of the spreadsheet. Somewhere in the bowels of Zhongnanhai, analysts are updating their “waiting‐it‐out” strategies.

For the rest of the planet, Grassley is a living experiment in gerontocracy, a walking stress test for democratic institutions that were designed when “life expectancy” still sounded like an optimistic oxymoron. The Senate’s average age now hovers around 64—roughly the retirement age in Sweden—yet Grassley’s daily schedule would exhaust most thirty-year-olds. He begins with a 4 a.m. jog, tweets cryptic koans about the History Channel (“watchin 1920s gangsters”), then spends the day interrogating Cabinet nominees with the cheerful menace of a farmer inspecting a suspicious heifer. Foreign diplomats confess a perverse comfort in dealing with him: unlike their own politicians, who pivot every news cycle, Grassley has been mad about ethanol subsidies since before ethanol was cool.

Of course, longevity has its perks. Grassley chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee whenever Republicans hold the majority, a post that lets him sculpt federal courts the way a bonsai master clips tiny trees. Every Supreme Court confirmation battle becomes a planetary spectacle; world leaders stream C-SPAN the way normal people binge Netflix. When Grassley slow-rolled Merrick Garland in 2016, European newspapers ran explainers titled “Why One Man in Iowa May Outlaw Abortion in America.” The irony was not lost on Parisian editorialists who still can’t believe a single senator from a state with more hogs than humans has veto power over global jurisprudence.

Yet for all the jokes—Twitter memes of Grassley riding a velociraptor, Chinese state media calling him “the last Qing dynasty senator”—his persistence highlights a darker truth about modern democracy: institutions ossify when voters prefer familiar brands to fresh ideas. In a year when Taiwan elected a 64-year-old former epidemiologist and France flirted with a 28-year-old rabble-rouser, the U.S. offers a nonagenarian plough horse. The global takeaway is less about Grassley than about the system that refuses to let him pasture. Autocrats in Ankara and Moscow must marvel at how America voluntarily freezes itself in amber, then congratulates itself on stability.

At press conferences, Grassley still answers questions with the same Midwestern cadence he used to grill Iran-Contra witnesses in 1987. Ask him about climate change and he’ll pivot to wind turbine blade disposal; ask about TikTok and he’ll muse about the Farm Bureau. It’s as if the world has been spinning but Chuck hit the pause button sometime around the Berlin Wall’s demolition. The joke, perhaps, is on us: while Silicon Valley promises eternal life via blood boys and biohacking, here is a man achieving it the old-fashioned way—sheer stubbornness and Iowa pork tenderloin.

So the international community watches, half in awe, half in dread, as the Senate’s Methuselah shuffles toward another decade. Foreign policy analysts have begun adding “Grassley factor” to their risk matrices; bookmakers now take prop bets on whether he will outlast the British monarchy. In the end, the joke writes itself: democracy is the only system where voters can choose a leader older than the ballpoint pen—and then act surprised when he files his expenses in triplicate.