Manny Machado’s $350M Ballet: How One Infielder Became a Global Economic Indicator

Manny Machado and the Global Theater of Overpaid Limberness

By Santiago “Sully” Márquez, International Sports Misanthrope

Somewhere between the Panama Canal’s perpetual bottleneck and the lithium mines that keep your smartphone humming, Manny Machado continues to bend his 6’3″ frame into positions that would make a Cirque du Soleil accountant blush. To the uninitiated, he is merely a third-baseman for the San Diego Padres. To the rest of us—jet-lagged souls who measure currencies in frequent-flyer miles and existential dread—he is a living allegory for a planet that has decided spectator contortion is worth more than, say, pediatric oncology.

In Tokyo, where the Yen flirts with historic lows, fans stream grainy highlights of Machado turning a 98-mph fastball into a souvenir. They do so while standing in 7-Eleven lines that snake past shelves of $2 bottled water and $40 melons, a pricing scheme that makes even Machado’s $350 million contract look refreshingly honest. The irony, of course, is that the same algorithmic magic that once guided Japanese manufacturing prowess now guides Statcast’s worship of launch angles—proof that the export of American leisure has become as reliable as its export of inflation.

Head north to South Korea, where the KBO League’s bat flips are national art, and Machado’s stoic glare is studied like a defecting diplomat’s memoir. Scouts there track his every hesitation step the way Seoul’s intelligence services track Kim Jong Un’s new hobby drones: with equal parts envy and strategic necessity. After all, if your geopolitical future depends on soft-power exports—K-pop, kimchi, and now maybe infield footwork—then every pirated MLB clip is both cultural victory and quiet surrender.

But the true international subplot unfolds in the Dominican Republic, the tiny island that annually supplies 10% of Major League rosters while negotiating with the IMF for a loan the size of Machado’s deferred signing bonus. In San Pedro de Macorís, boys who share his surname but not his agent practice pivots on dirt infields that double as goat pastures. Their bats are repurposed boat oars; their dreams, amortized over 30 years with a team option for despair. When they see Manny nonchalantly spear a grounder bare-handed, they also see the invisible scaffolding of American academies, immigration attorneys, and the ever-cheerful ghost of colonial extraction. It’s baseball’s version of the Dutch East India Company, only with more Gatorade flavors.

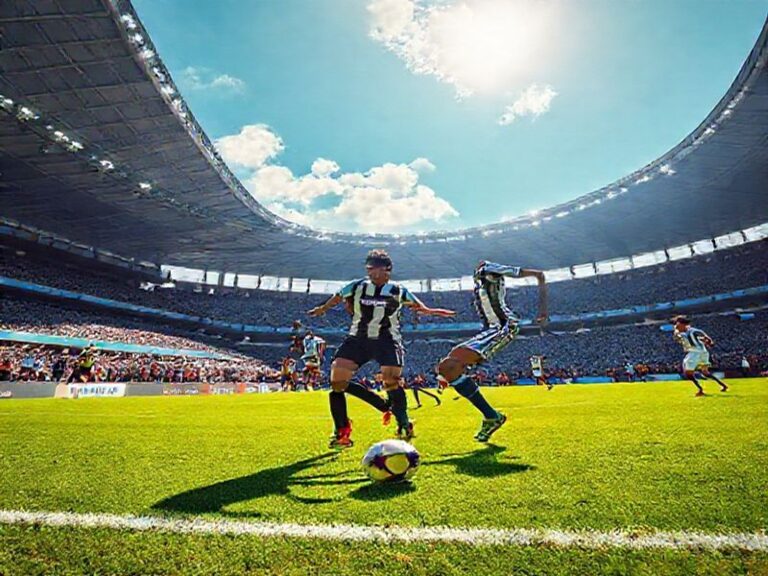

Europe, bless its smug heart, pretends not to care. Yet in London’s Olympic Stadium—where the NFL now stages taxpayer-subsidized exhibitions—British fans who once dismissed rounders now argue whether Machado’s defensive WAR justifies his merch markup in pounds sterling. Brexit may have severed the continent, but a bobblehead is still a bobblehead, and irony, like COVID, is happily passport-free.

Meanwhile, the climate clock ticks louder than any walk-up song. Machado’s private jet burns roughly 400 gallons an hour, enough to power a Filipino fishing village for a month. Each cross-country road trip thus becomes a floating carbon offset commercial nobody asked for, narrated by a league that just signed an exclusive streaming deal with a tech giant currently lobbying against right-to-repair laws. Somewhere, a polar bear files a grievance.

And still, the man plays on. When he corkscrews into the hole to rob a hit, global supply chains shiver in solidarity: Taiwanese microchips, Guatemalan stitching, and a Dominican smile stitched into every flagship glove. The ball ends up in the stands; the labor ends up in quarterly reports.

Conclusion: Machado’s nightly acrobatics are less a sports page headline than a quarterly earnings call performed in cleats. In a world where a shortstop’s lateral quickness is tracked by satellites originally designed to spot missile launches, perhaps the most honest box score is this: one human body, 31 years old, leveraged at roughly $11.3 million per WAR, orbiting a planet whose own rotation seems increasingly negotiable. The crowd cheers, the stockholders cheer louder, and somewhere a child with a boat-oar bat calculates the exit velocity of hope. Play ball, indeed.