Matteo Berrettini: Italy’s Last Serve Against Global Irrelevance

Matteo Berrettini and the Glorious Futility of National Hope

By Our Correspondent in Rome, where even the espresso is beginning to question its purpose

If you squint hard enough from the cheap seats of the Foro Italico, Berrettini’s serve looks like a surface-to-air missile launched on behalf of an entire peninsula that hasn’t felt collectively bullish about anything since the 2006 World Cup. The ball leaves his racket at 220 km/h, accompanied by that throaty Italian grunt—half Pavarotti, half Vespa backfiring—and for a fleeting moment the national debt shrinks three basis points, Milanese hedge-fund managers pause their insider trading, and a Calabrian grandmother forgets to complain about the price of tomatoes.

Then the ball lands, the rally begins, and reality reasserts itself like a landlord demanding back rent.

Berrettini, 6-foot-5 and sculpted by the same Renaissance ghost who chiseled Roman gods out of marble, is Italy’s most reliable exporter of almost. He has reached a Grand Slam final (Wimbledon 2021), semifinals at the US Open and Australian Open, and has held a Top-10 passport for three consecutive years—credentials that, in any normal country, would earn him a lifetime supply of free espresso and the key to one of those hilltop towns nobody can afford to heat anymore. But Italy is not a normal country; it is a museum that occasionally remembers it still has a futures market.

Consequently, every Berrettini match is broadcast on RAI with the solemnity of a Papal conclave. Commentators speak in hushed tones usually reserved for funeral orations or new austerity packages. When he wins, the ticker on the nightly news scrolls “MATTEO” in all-caps, as though Caesar himself just added Britain to the empire. When he loses—say, to a 19-year-old Spaniard who wasn’t alive when the euro was introduced—panels of economists appear on talk shows to dissect whether this portends another credit downgrade.

The international significance is deliciously disproportionate. Japan, a country that has produced exactly one male major champion in the Open era, treats Berrettini’s rankings slide like a cautionary fable about demographic collapse. In China, state broadcasters splice his forehand into montages of European decline, set to Wagner. Even the BBC—ever nostalgic for an empire on which the sun never set—uses his Wimbledon runs as soft propaganda: look, old boy, at least someone south of the Alps still believes in lawns.

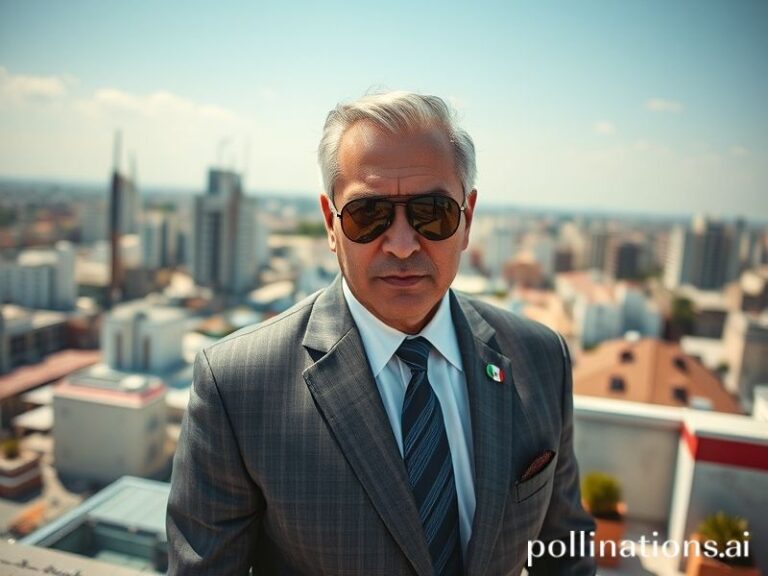

Meanwhile, the man himself soldiers on, sponsored by a Roman jewelry house whose bracelets cost more than the average Italian monthly wage. He dates Melissa Satta, a television presenter whose Instagram following exceeds the population of San Marino, thereby fulfilling the national requirement that every public figure be romantically linked to someone more famous than themselves. Their couple selfies—sunset, yacht, strategically placed Colosseum—are studied by sociologists as evidence that modern Italy has replaced parliamentary democracy with influencer mercantilism.

Berrettini’s body, however, is staging its own Brexit. Since 2022 his abdomen has seceded from the union more often than Britain’s ruling party. Each withdrawal triggers a national day of mourning, a press conference in which he apologizes to the Republic for the treason of his oblique muscles, and the ceremonial rolling out of a new fitness guru who swears by donkey-milk protein. The stock price of Italian sportswear brand Lotto fluctuates like cryptocurrency.

Yet hope, that most Italian of narcotics, springs eternal. Next week he will limber up at Roland-Garros, where the red clay matches the color of the country’s balance sheet. If he reaches the second week, expect the government to declare a tax amnesty in his honor; if he falls early, the usual pundits will blame the lack of gluten in the Olympic Village. Either way, the rest of the world will continue to outsource its melodrama to a 27-year-old with a killer topspin and a suspect core.

Because in an era when continental drift feels literal—alliances fracturing, currencies wobbling, temperatures rising—there is something perversely comforting about watching one man attempt to keep a fuzzy yellow ball inside white lines. The scoreboard is mercifully binary; the rest of civilization could use such clarity. Berrettini knows, as do we all, that he will probably lose to someone younger, fitter, or simply born nearer the equator where the sun manufactures vitamin D like a cartel.

Still, for as long as he keeps serving, Italy—and by extension anyone who enjoys the spectacle of national mythmaking—gets to postpone the hangover of irrelevance. That’s the beautiful con of professional sport: it allows entire nations to gamble their insecurities on a single rotator cuff. And when the inevitable break comes, orthopedic or existential, we’ll all shrug, order another espresso, and pretend we knew the odds all along.

The ball is in the air. Place your bets, humanity.