Gael Monfils: The Last Globetrotting Jester in Tennis’s Age of Robots

Gael Monfils, the human highlight reel currently moon-walking his way through what polite society still calls “the twilight of his career,” is tennis’s last living reminder that the sport was once supposed to be fun. While the rest of the men’s tour has been busy cloning 6-foot-6 Balkan metronomes who hit the ball as if it owes them rent, Monfils—age 37 going on 17—continues to treat every rally like an audition for Cirque du Soleil. The Frenchman’s elastic legs and apparent allergy to common sense have turned even routine first-rounders into global GIF summits, streamed from Cincinnati to Cairo by office workers who should probably be doing something more productive, like pretending to work.

International audiences project onto Monfils what they can no longer find at home. In Tokyo salarymen see the rebellion they surrendered at the commuter-rail gates. In Lagos cyber-cafés he’s proof that Black athletic genius can still flourish without being strip-mined by European football academies. And in suburban London, Brexit retirees—who voted to keep people like him out—now cheer his behind-the-back tweeners with the same fervor they reserve for complaining about the price of imported camembert. Irony, unlike Monfils, is not ageing gracefully.

The broader significance, if we absolutely must pretend tennis matters outside the two-week Wimbledon gin-soak, is that Monfils offers the last unbranded joy in a sport increasingly micromanaged by analytics departments who measure “grin ROI” and instruct players to smile only on odd-numbered Tuesdays. While the tour’s NextGen are drip-fed data on optimal sleep cycles and carbohydrate windows, Monfils still prepares for matches by dancing alone to Congolese rumba in the locker room mirror, presumably asking himself whether a between-the-legs half-volley is really necessary at 15-40. (The answer, of course, is always yes.)

Bookmakers in Malta list Monfils as a 50-1 long shot to win any given major, odds roughly equivalent to the United Nations passing a meaningful resolution before lunchtime. Yet the betting handle on him remains stubbornly high, because humans—despite mounting evidence to the contrary—persist in believing that style might still defeat spreadsheet. It won’t, but watching Monfils chase down a drop shot with the urgency of a man fleeing his own tax audit is the closest modern sport comes to affordable existential theatre.

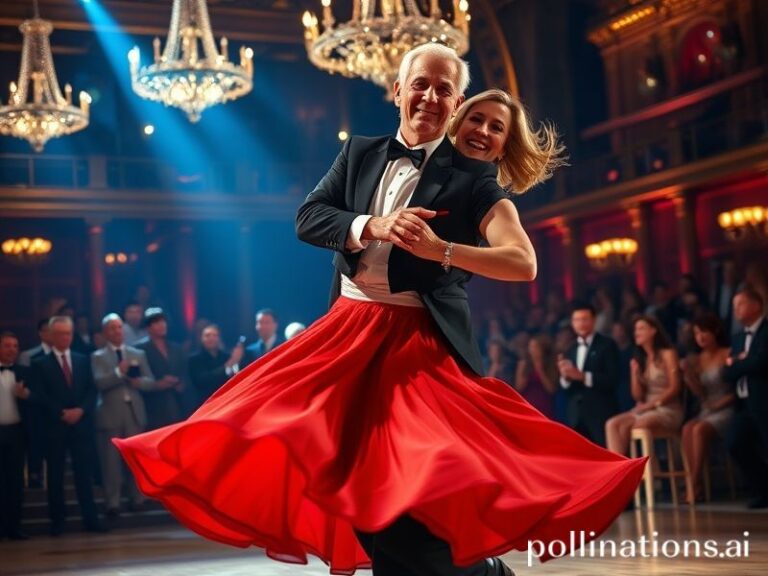

Off-court, Monfils is married to Elina Svitolina, Ukraine’s former world No. 3. Their Instagram coupling—he posts dad-joke captions in franglais, she replies with eye-roll emojis—has become a rare soft-power win for Europe: proof that even in a continent fracturing along every possible fault line, love still finds a way to schedule joint practice sessions between missile alerts and sponsorship dinners. The Kremlin, one suspects, has yet to weaponize a meme featuring Monfils doing the worm across Roland-Garros clay, but give it time.

Global brands, those reliable vampires of authenticity, have noticed. Swiss watchmakers who normally require at least one felony conviction for ambassadorship now court Monfils, correctly deducing that irreverence sells in an era when the average consumer would rather floss with barbed wire than watch another perfectly scripted athlete video. The result: a recent ad in which Monfils vaults over a net to high-five an AI hologram of himself, tagline “Time is elastic”—a sentiment so nakedly absurd it loops all the way back to genius, much like his on-court logic.

As climate change nudges outdoor tournaments toward the Arctic Circle and geopolitical tensions threaten to fracture the tour into regional bubbles, Monfils remains a one-man argument for keeping the circus on the road. The man has already outlasted three French presidents, two pandemics, and one rogue line judge who tried to card him for excessive charisma. Should he finally retire, the sport will be left with nothing but baseline robots and the faint smell of burnt rubber where joy used to live.

Until then, the planet spins, governments fall, and somewhere in a stadium lit like a dystopian disco, Gael Monfils is sliding into a split to retrieve a ball he had absolutely no right to reach—reminding us, briefly, that the end of the world might at least be entertaining.