Daria Kasatkina: The Russian Tennis Star Playing Against Putin, Prejudice, and Prize Money in Equal Measure

Daria Kasatkina is not the tennis story most broadcasters lead with. She doesn’t smash rackets, date pop stars, or hire an entourage the size of a NATO battalion. Instead, the 26-year-old Russian has spent the last year turning press conferences into miniature Nuremberg trials—minus the dramatic lighting—while still finding time to dispatch top-ten opponents with the serene detachment of someone cancelling a dinner reservation. In a sport that prefers its rebels safely marketable, Kasatkina’s crime is sincerity, a commodity so scarce that the WTA Tour now treats it like a banned substance.

Let’s set the geopolitical stage, shall we? Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned every Russian athlete into an unwilling ambassador—either a plucky exile or a Kremlin sock puppet, depending on your cable package. Wimbledon, in its infinite British wisdom, solved the dilemma by banning Russians entirely, thereby protecting the hallowed grass from ideological weeds. Kasatkina responded by posting an Instagram story of herself sipping coffee in Barcelona, caption: “Grass is overrated anyway.” Subtle as a drone strike, that one.

Her real offense, though, was coming out last July—first as gay, then as comprehensively fed-up with her homeland’s trajectory. Imagine the scene: a Russian athlete admitting she has a girlfriend the same week the Duma expanded its “gay propaganda” law to cover everything except breathing. State television immediately re-edited her match highlights into a fever dream of moral decline: backhand equals Western decadence, forehand equals Satan. Viewers were advised to clutch their children and their pearls simultaneously.

Western audiences, eternally thirsty for dissident chic, embraced her with the fervor of a Black Friday sale. LGBTQ+ NGOs slapped her face on fundraising emails; think-pieces crowned her “the bravest athlete alive,” which is a bit like calling someone the tallest Ewok. Meanwhile, the WTA—an organization that once staged a tournament in Riyadh with a straight face—issued a statement “recognizing her courage,” corporate speak for “please don’t look at our Qatari sponsorships.” The hypocrisy is so thick you could spread it on toast, but hypocrisy is the universal currency; only the exchange rate varies.

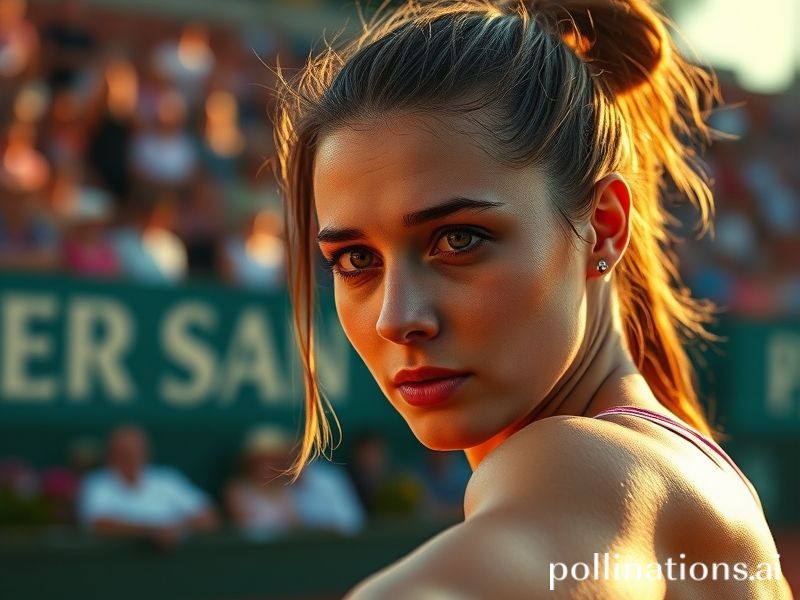

On court, the irony sharpens. Kasatkina plays a brand of tennis that would make a chess grandmaster weep: angles tighter than a Moscow studio apartment, drop shots that land like bad news. She’s currently ranked No. 8, having demolished Iga Świątek in the Stuttgart final with the casual cruelty of someone swatting a fly. Yet prize money is paid in dollars, sponsorships in euros, and Russian players still can’t compete under their own flag. So she walks out behind a white flag—literally, the “neutral athlete” banner, which looks suspiciously like surrender. History will note the symbolism; the commentators will note her second-serve percentage.

Off court, the sanctions regime has made her an unwilling expert in offshore finance. Appearance fees are routed through Dubai; coaching staff paid via Istanbul; even her racquet stringer now demands payment in cryptocurrency, presumably to launder the moral ambiguity. When asked if she misses home, Kasatkina shrugs: “I miss my dogs. The rest is geography.” The line travels so well it ought to have its own passport.

The broader significance? In a world where nations weaponize everything from gas pipelines to Eurovision votes, Kasatkina is a walking contradiction: a Russian who rejects Russia, a lesbian embraced by sponsors who’d fire her if ratings dipped, an athlete excelling in a system that can’t decide whether to celebrate or erase her. She is, in other words, the perfect emblem of our fractured century—competing under no flag but her own, and even that one is under review.

So when the next Grand Slam rolls around and the cameras zoom in on her expressionless face, remember: you’re not just watching tennis. You’re watching a woman play three-dimensional chess against history, nationalism, and late-stage capitalism—all while keeping her first-serve percentage above 65%. If that isn’t sport, nothing is.