Global Immunity: How the CDC’s Needlework Quietly Holds the Planet Together

**Global Immunity: How the CDC’s Needlework Quietly Holds the Planet Together**

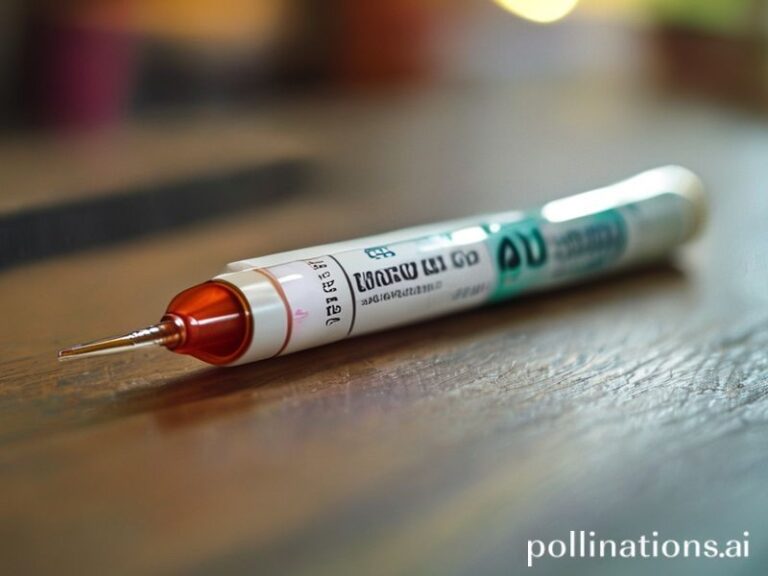

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, headquartered in a glass-and-steel fortress in Atlanta, is the world’s most unlikely superhero—no cape, just a clipboard and a fridge full of chilled vials. While other nations fund aircraft carriers or Olympic stadiums, the United States has bankrolled a bureaucracy whose deadliest weapon is a 0.5-mL dose of attenuated virus. The payoff? A geopolitical insurance policy so understated that most people only notice it when a new pathogen starts trending on Twitter.

Internationally, the CDC’s vaccine playbook is photocopied, translated, and occasionally smuggled across borders like samizdat literature. When Brazil’s Ministry of Health needs to know how many micrograms of mRNA will keep Carnival from becoming a superspreader sequel, they call Atlanta. When the Congolese village of Ingende wonders whether the local bat colony is a viral slot machine, CDC freezer trucks arrive before the Chinese infrastructure loans do. The message is subtle but unmistakable: hegemony today is measured less in aircraft carriers and more in cold-chain logistics.

Of course, global gratitude lasts about as long as a Pfizer booster in a rural clinic. France will toast American science while simultaneously suing it for patent infringement. Russia will praise CDC data even as its state channels blame the Pentagon for every sneeze in Siberia. And everywhere, anti-vax influencers—many funded by the same regimes that quietly import those very vaccines—warn that the shots contain 5G chips, mind-control nanobots, or, worse, high-fructose corn syrup. Humanity’s capacity for cognitive dissonance, it seems, is the only disease we’ve truly eradicated nowhere.

The financial choreography is equally farcical. COVAX, the multilateral effort to vaccinate the world’s poor, has spent two years playing an epidemiological version of musical chairs: donors pledge billions, manufacturers raise prices, and cargo planes full of soon-to-expire doses circle African capitals like vultures with boarding passes. Meanwhile, the CDC quietly underwrites the surveillance networks that tell us when a new variant is cooking in Gauteng or Gujarat—intel that Moderna and Pfizer then monetize faster than you can say “public-private partnership.” If irony were a tradable commodity, we’d have vaccinated the entire Global South with it by now.

Still, the numbers refuse to be cynical. Measles deaths down 94 percent since 2000; polio cornered into two remaining provinces; smallpox eradicated so thoroughly that the only place you can still catch it is a Soviet-era lab freezer. These victories are posted on the same internet that insists the Earth is flat and Bill Gates is magnetizing your spleen. Somewhere in the metaverse, an avatar is selling NFTs of the smallpox virus; back on Earth, a Bangladeshi child receives a measles shot for free and lives long enough to hate TikTok dances.

The broader significance? In an era when climate change promises to thaw ancient pathogens like microwaved leftovers, the CDC’s vaccine infrastructure is the closest thing humanity has to a planetary immune system. It’s imperfect, underfunded, and occasionally hijacked by politicians who think “peer review” means asking donors what they think. But it is also the reason your last flight didn’t double as a measles party at 30,000 feet, and why Brazilian virologists can sequence a novel coronavirus faster than you can cancel your cruise reservation.

So here’s to the bureaucrats with frostbitten fingers counting doses at 3 a.m., to the epidemiologists who speak fluent variant, and to the cargo pilots who treat every broken cold box like a failed organ transplant. They know that pandemics are just climate change in a hurry: borderless, indifferent, and spectacularly unimpressed by your sovereignty. The CDC’s vaccines may not save us from ourselves—nothing short of a firmware update for human nature could manage that—but they do buy us just enough time to argue about the next catastrophe. And in this century of rolling crises, that’s as close to a happy ending as the species gets.