The Czechoslovakia Letter: How a 30-Year-Old Envelope Became the World’s Newest Political Football

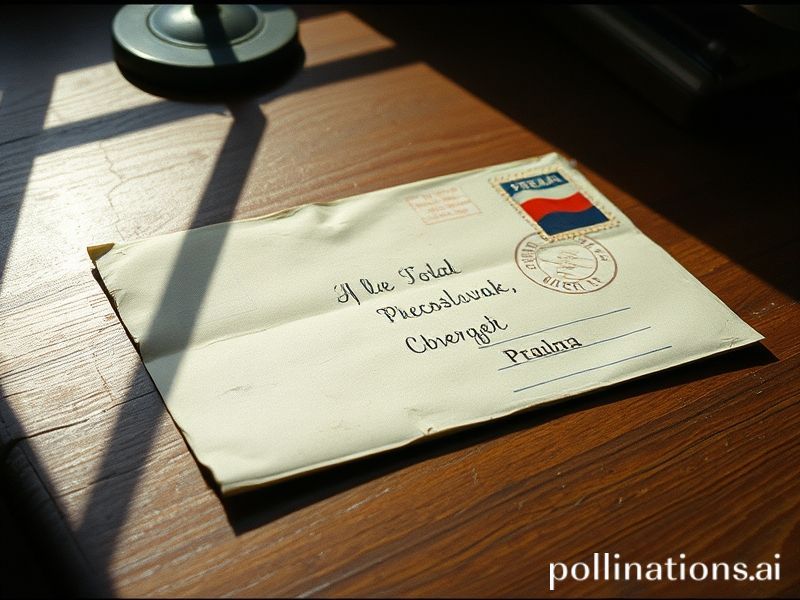

PRAGUE—The envelope, yellowed like a chain-smoker’s thumbnail, arrived in the Czech postal service’s dead-letter office sometime after the Velvet Divorce of ’93. Addressed simply to “Czechoslovakia,” it sat in bureaucratic purgatory for thirty-one years—long enough for the Iron Curtain to rust into garden trellises, for the euro to replace dreams, and for TikTok to convince teenagers that history is a filter. Last week, a bored clerk with nicotine fingers finally slit it open, releasing what the foreign press has breathlessly dubbed “The Czechoslovakia Letter,” as though Kafka had left a Post-it for future civilizations.

Inside: a single sheet of onionskin, typed on a machine that predates spell-check, signed “M.” It reads less like state secrets than a shopping list scrawled by someone who’s just realized the store no longer exists. “Don’t forget the uranium in Jáchymov,” it reminds. “Also, the Slovaks are right about the dam.” The tone is oddly tender, the geopolitical equivalent of “Wish you were here” written from a country that has, in fact, checked out.

Instantly, the world’s commentariat smelled blood in the water—or at least nostalgia in the ink. Washington think-tankers, still hungover from the last NATO birthday bash, proclaimed the letter proof that post-Soviet borders remain “narrative play-dough.” Beijing’s wolf-warrior diplomats retorted that if letters can resurrect nations, then Taiwan should start licking envelopes. Meanwhile, Elon Musk tweeted a Photoshopped Czechoslovakia-shaped Tesla, because nothing says “future” like commodifying yesterday’s heartbreak.

Across Europe, the discovery triggered the continent’s favorite pastime: collective navel-gazing at 3 a.m. Berliners queued outside former Checkpoint Charlie to mail their own cryptic notes to “Prussia.” In Brussels, EU officials convened an emergency committee to regulate the emotional residue of defunct states; the proposal will be ready sometime around the heat death of the universe. And in Britain—ever the trendsetter—Brexiteers began drafting letters to “The British Empire,” postage prepaid by colonial amnesia.

The broader significance, if one is sober enough to squint, is that the letter exposes our peculiar twenty-first-century addiction to retro geopolitics. We binge-watch the Cold War on Netflix, cosplay revolutions on Instagram, and trade USSR memorabilia on Etsy while actual tanks roll through actual borders elsewhere. The Czechoslovakia Letter is not a message; it’s a mirror, reflecting a planet nostalgic for binaries it spent decades dismantling. We miss having one big, obvious enemy so much we’re willing to Frankenstein one from archival dust.

Financial markets, never ones to miss a good delusion, have already launched the “Czechoslovakia Futures Index,” tracking theoretical GDP if the federation had stayed together and discovered offshore Bitcoin deposits. Analysts at Goldman Sachs issued a 200-page report titled “Reunification Arbitrage,” which concludes—after exquisite jargon—that the best investment is denial. Naturally, the index surged 12 % on opening day, then fell 14 % when someone pointed out that neither Prague nor Bratislava can agree on whose anthem to play at the IPO bell.

Human rights lawyers, bless their evergreen optimism, argue the letter revives questions of citizen identity erased by partition. What happens to the stateless nostalgia of people born in a country that no longer issues passports? The International Court of Justice in The Hague has scheduled hearings for 2027, or whenever the coffee machine is fixed—whichever comes first.

At the dead-letter office, the clerk who opened the envelope has become an unwitting celebrity. He shrugs at cameras, chain-smokes the same brand as the envelope, and mutters that history smells like wet wool and regret. Asked what should happen to the letter, he suggests forwarding it “to the last known address of the 20th century.” The postal service, ever dutiful, has stamped it “Return to Sender—Address Unknown.”

And so the Czechoslovakia Letter re-enters circulation, a paper ghost hitching rides on our collective guilt trips. It may never arrive anywhere, but it guarantees one thing: the world will keep circling the drain of its own contradictions, forever licking stamps for countries that have already checked out of the hotel we’re all still paying for.