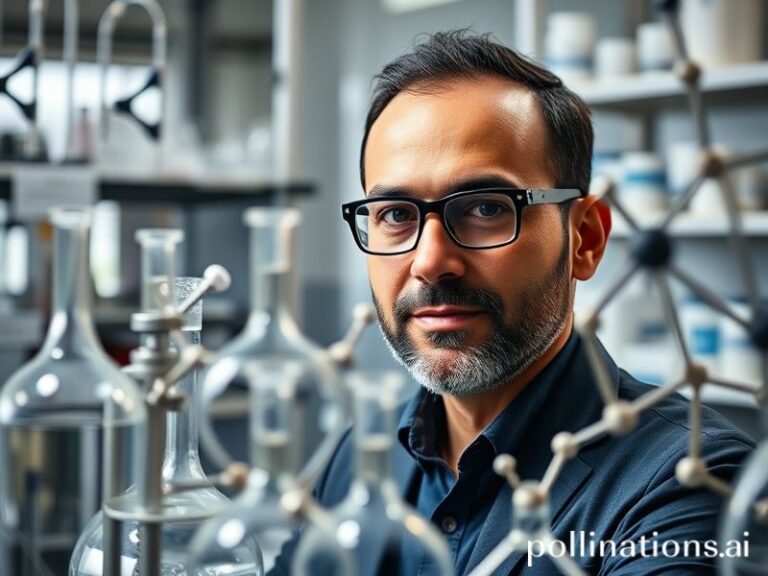

john sununu

John Sununu: The Man Who Made Bureaucracy a Contact Sport

By Dave’s Locker International Affairs Desk

On the surface, John H. Sununu looks like the sort of technocrat who could be quietly misplaced behind a potted palm at any OECD reception. A former governor of New Hampshire, White House Chief of Staff to George H. W. Bush, and MIT-trained mechanical engineer, Sununu is the rare figure who can argue thermodynamics at breakfast and still have enough rhetorical heat left to scorch a congressional committee by lunch. Yet from Brussels to Beijing, the mere mention of his name triggers a Pavlovian smirk among policy watchers—part nostalgia, part schadenfreude, part “there, but for the grace of term limits, goes the rest of us.”

Sununu’s résumé reads like a cautionary syllabus for globalization’s seminar on hubris. In 1989, while Europe was busy pantomiming the end of history, Sununu was stateside perfecting the art of the political body-check. He reportedly commandeered Air Force jets for personal ski weekends—because nothing says “public service” like burning 5,700 gallons of JP-8 to carve fresh corduroy in Vail. The scandal cost him altitude, though not, curiously, his pilot’s license for hypocrisy: he simply walked the plank into cable-news punditry, where carbon footprints are counted only in Nielsen ratings.

From a global vantage, Sununu’s trajectory offers a master class in how American political talent is recycled more efficiently than Scandinavian aluminum. Japanese bureaucrats retire into windowless advisory sinecures; French politicos parachute into boardrooms of state-owned energy giants; but only in the United States can you rocket from West Wing enforcer to—voilà—paid savant on networks that still spell “colour” without the “u.” The planet watches in bemusement: one nation’s administrative malpractice is another’s prime-time entertainment export.

Sununu’s current incarnation as combative TV surrogate is instructive for emerging democracies still learning that democracy is less “government by the people” and more “government by the people who can book green rooms.” When he sparred with CNN hosts over the Mueller probe, Macedonian teens streaming the clip recognized the playbook: shout over the moderator, brandish a single data point like a broken bottle, declare victory on Twitter. In a world where Myanmar’s generals binge-watch American news to calibrate their own press briefings, Sununu’s performances are effectively U.S. soft power—just not the sort anyone at Foggy Bottom is eager to claim.

Internationally, the former governor’s legacy is a Rorschach test. Germans admire his engineering pedigree yet wince at his disdain for emissions etiquette. Singaporeans applaud his ruthless staff management—legend has it he once dismissed an aide for mispronouncing “nuclear”—while privately calculating how many canings such insolence would earn on their island. In Nairobi tech hubs, Sununu is cited as proof that STEM brilliance and climate denial can coexist in one carbon-based life form, a cautionary tale for start-ups betting on solar micro-grids.

What makes Sununu globally resonant is his embodiment of late-capitalist paradox: the more systems you understand, the less inclined you are to fix them. In 1991 he co-authored a paper on thermodynamic efficiency; a year later he was scuttling fuel-economy standards with the enthusiasm of a man who’d just discovered the laws of political entropy. Abroad, this reads as a uniquely American magic trick—pulling gridlock out of a hat while claiming it’s bipartisanship. British civil servants call it “doing a Sununu” whenever a minister shelves a green initiative after lunch with oil lobbyists.

And so the world spins on, warmed—literally—by such contradictions. Sununu remains the patron saint of technocratic nihilism: smart enough to know the ice caps are melting, connected enough to ensure the water reaches the poors first. Viewed from Davos, he is a geopolitical heat pump, redistributing blame from north to south. From Lagos traffic jams to La Paz water riots, his fingerprints—indirect, immaculate, and carbon-dated—linger like cheap cologne in an elevator no one can exit.

In the end, John Sununu teaches us that global influence rarely arrives wearing a hero’s cape; more often it sports a frequent-flyer lanyard and a smug grin. The planet’s takeaway? If you can’t beat the system, at least expense the mileage. And remember: somewhere, in a language you don’t speak, your worst political punch line is someone else’s prime-time tutorial.