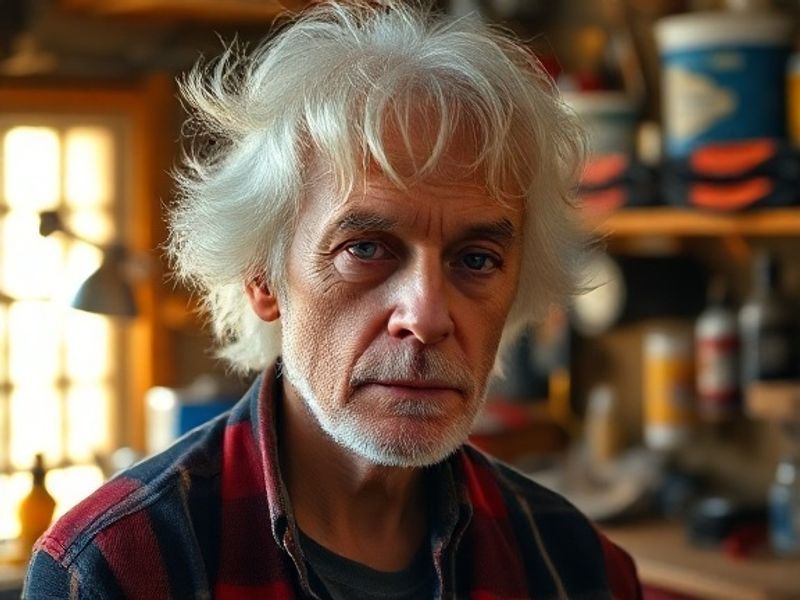

Christopher Lloyd at 85: How One Mad Scientist Became the Global Patron Saint of Unintended Consequences

Christopher Lloyd: The Man Who Put Time Travel on the Global Balance Sheet

By Our Man at the End of the Universe

PARIS—While most of the planet’s 8.1 billion souls were busy doom-scrolling through inflation charts and celebrity divorces last week, one Christopher Lloyd quietly celebrated his 85th birthday. Not the disgraced FTX coder, mind you, but the other one—the wild-eyed physicist who taught the world that the only difference between a DeLorean and a diplomatic summit is 1.21 gigawatts and slightly better lighting.

For anyone born after the Berlin Wall fell, it’s hard to explain how a single American character actor became an unwitting prophet of late-stage capitalism. In 1985, Lloyd’s Emmett “Doc” Brown looked like harmless comic relief, an eccentric uncle who’d misplaced his lithium. Now, in 2024, he reads like a venture-capital pitch deck. Replace plutonium with ESG credits and the flux capacitor with blockchain, and Doc is basically any Tech-Bro Messiah promising to disrupt linear time for Series C investors. The irony, of course, is that the man himself still lives in Montana, drives a Prius, and regards Tesla owners the way ornithologists regard pigeons: mildly interesting, mostly diseased.

Globally, the Doc Brown archetype has become a kind of diplomatic Esperanto. In Seoul, policy wonks cite his “roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads” line to justify hyperloop budgets. In Brussels, the line is printed on mouse pads in the Directorate-General for Mobility—right next to the reminder that the trains still don’t run on time. Even the Kremlin got in on the act: state television once superimposed Lloyd’s face onto a Sarmat missile launch, subtitled “Back to the USSR.” The joke bombed domestically—Russians prefer their nostalgia without plutonium—but it trended on Telegram for a solid afternoon, which in modern geopolitics counts as soft power.

Economists, ever eager to monetize childhood trauma, have calculated that the Back to the Future trilogy added $2.7 trillion in intangible value to the global economy. How? Merchandise, theme-park rides, and the unquantifiable boost to DeLorean restorers who now sell “authentic time-machine conversions” for the price of a Bucharest condo. Meanwhile, actual physicists at CERN use the films in PowerPoint slides to secure funding for experiments they privately admit will never outrun thermodynamics. Somewhere in Geneva, a post-doc is updating her LinkedIn: “Experience: Helped discover Higgs boson; also consulted on temporal paradoxes, will time-travel for visa sponsorship.”

The darker joke is that Doc Brown’s original sin—stealing plutonium from Libyan nationalists—now looks quaint. In 2024, rogue states outsource their uranium enrichment to dating apps and deliver payloads via Amazon Prime. Lloyd never predicted drone strikes, only hoverboards, and even those turned out to be flaming death traps sold at half price on Alibaba. Watching the films today feels like reading a prophecy written on a bar napkin: half right, half spilled beer, entirely too late.

Still, the man endures. Ukrainians have memed him into a St. Javelin-style icon: “Doc Brown delivers HIMARS instead of hover conversions.” In Tokyo, salarymen wear “Great Scott!” ties to shareholder meetings, a small rebellion against lifetime employment. And somewhere in Lagos, a generator mechanic has spray-painted “88 MPH OR BUST” on a shack, because diesel is cheaper than optimism and both run out eventually.

So raise a glass—preferably something non-irradiated—to Christopher Lloyd, accidental cartographer of humanity’s midlife crisis. He gave us a map to the future, and we used it to circle back to the same old parking lot. As Doc himself might say, staring at the smoldering wreckage of yet another timeline: “Well, that’s progress for you—always crashing in the same car.”