Shane Warne: The Aussie Who Bowled the World into One Shared Gasp

Shane Warne: How a Man in Cream Whites Turned Cricket into Global Schadenfreude

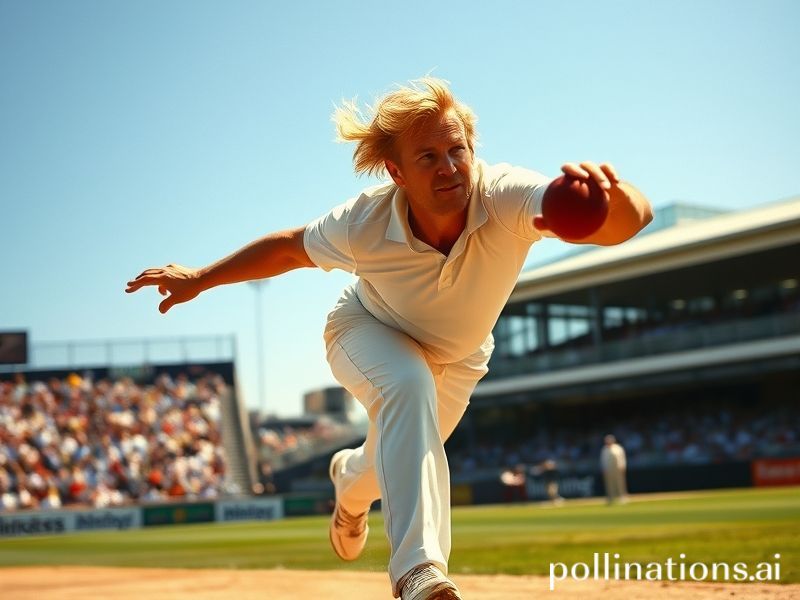

When Shane Warne bowled “the ball of the century” at Old Trafford in 1993, the planet was still divided into neat Cold-War time zones, dial-up internet sounded like a dying modem, and the phrase “global superstar” was reserved for Michael Jackson and any dictator with a decent tailor. Yet with one drifting, dipping, impossibly vicious leg-break that clipped Mike Gatting’s off-stump like a pickpocket lifting a wallet, Warne did something the United Nations never quite managed: he made the whole world lean in at the same moment. Thirty-one years later, his death in Thailand—reportedly after a night of the usual Warnie cocktail of cigarettes, Instagram filters, and misplaced immortality—felt less like the passing of a sportsman and more like the unplugging of a universal Wi-Fi router. Suddenly, everyone from Mumbai baristas to Murmansk truckers had a hot-take about wrist spin and late-night room-service calamari.

In an era when nations outsource their existential dread to TikTok trends, Warne’s genius was refreshingly analogue: a fat bloke in zinc cream who could make a leather sphere obey him like a Labradoodle on Xanax. He turned cricket—formerly the slowest export of the British Empire since the queue at Heathrow Passport Control—into a binge-watchable spectacle. Television rights for the Indian Premier League, essentially a Bollywood fever dream with scoreboards, now fetch billions. Analysts rarely admit it, but that valuation begins with Warne’s 1990s alchemy in converting five-day marathons into highlight-reel crack. The IPL’s current owners include a Saudi sovereign fund, a U.S. private-equity giant, and at least one Bollywood heart-throb who probably thinks a googly is an exotic cocktail. None of them send thank-you cards to a cemetery in Melbourne, but capitalism has always been lousy at acknowledgements.

Warne’s personal narrative was gloriously un-Instagrammable: booze, bookies, banter, and a texting habit that made the News of the World positively solvent. Yet the contradictions only enlarged the brand. Australians forgave him because he embodied the national fantasy: the larrikin genius whose appetites were as oversized as his talent. Indians worshipped him because he treated their batsmen with the respect of a man disarming nuclear codes. The English merely hated him, which in the post-Brexit economy counts as emotional GDP. When he died, the British tabloids ran 48-point headlines about “national mourning,” neatly forgetting that for two decades they had called him every synonym for “rotund” available in the OED.

The macro takeaway? In the attention economy, skill is merely the gateway drug; narrative is the fentanyl. Warne understood this before Silicon Valley had even invented the word “engagement.” His Twitter feed—equal parts poker tips, pizza endorsements, and philosophical musings on the forward-defensive—was a masterclass in monetising chaos. After his death, NFTs of that Gatting ball sold for sums that could bail out a small Greek island. Somewhere, Mike Gatting is still waiting for royalties.

Globally, Warne’s legacy is a cautionary parable about what happens when genius is granted diplomatic immunity from consequence. His body gave up at 52, which in modern actuarial terms is practically adolescence. Meanwhile, the sports-industrial complex he helped create now pumps out biomechanically optimised teenagers who hydrate better than most hospitals. The next Warne will probably be a 3-D-printed wrist-spinner from a Shanghai lab who never touches carbs. He’ll also have no anecdotes involving late-night Vegas roulette with DiCaprio, which means the sponsors will have to invent them.

In the end, the world didn’t just lose a cricketer; it misplaced the last rock-star athlete who could make geopolitics look irrelevant for five days (or at least until the next rain delay). Shane Warne proved that a man with nicotine-stained fingers could still spin the globe—clockwise, then the other way, then back again—until even the umpires forgot which way was north. The planet will keep turning, albeit with slightly less revolutions per minute.